Corticogenesis

Cortex topology and taxonomy

Adapted from illustrations of Nissl staining of adult M1 cortex by Ramon y Cajal (1911)

The mature cortex consists of billions of neurons organized into a six-layered (L 1-6) structure. These neurons interact via short and long-range connections to form the complex circuitry which results in the emergent property of cognition. This cortical layout is highly conserved across mammals1,2. The neurons of the cortex occupy two major classes, GABAergic (inhibitory; iN) and glutamatergic (excitatory), and from those two major classes, dozens to hundreds of subtypes form, identified through distinct neuronal processes, circuit membership and gene expression patterns3. Glutamatergic excitatory neurons possess axonal projections which synapse at various brain regions, and projection properties dominate cell type grouping in single-cell RNA data3. These neurons form circuits with their inputs serving to promote action potential firing and downstream neural activity. Typography and topography (i.e. cell type and location) inform neuron function. For instance, glutamatergic pyramidal tract neurons are most common in deep layer L5 (ventrally located) and are associated with executing voluntary movements and planning. These project to subcortical targets like the striatum, thalamus, tectum and pons4. In contrast, glutamatergic intratelenecephalic trajectories connect excitatory neurons between cortical layers or cortical brain regions, and span most layers3. GABAergic inhibitory neurons have two major subclasses which reflect their point of origin5. Adenosine Deaminase RNA Specific B2 (ADARB2+) expressing inhibitory neurons are formed in the caudal ganglionic eminence, whereas LIM Homeobox 6 (LHX6+) neurons form in the medial ganglionic eminence (CGE and MGE, respectively). Inhibitory neurons produce the small molecule GABA, and modulate neuronal circuitry through dampening neuronal firing. Glia, which have previously been considered to be connective cells, have been found to serve critical roles in maintaining synapse integrity and cortical function. Astrocytes mediate blood brain barrier and have been shown to mediate synapse formation, elimination, and plasticity. Oligodendrocytes enable salutatory conduction of actionable potentials throughout the brain. Microglia are resident immune cells, participate in phagocytosis and inflammation response. Neuronal circuitry is an active field of study – which benefits from understanding the unique states and types of neurons and glia6.

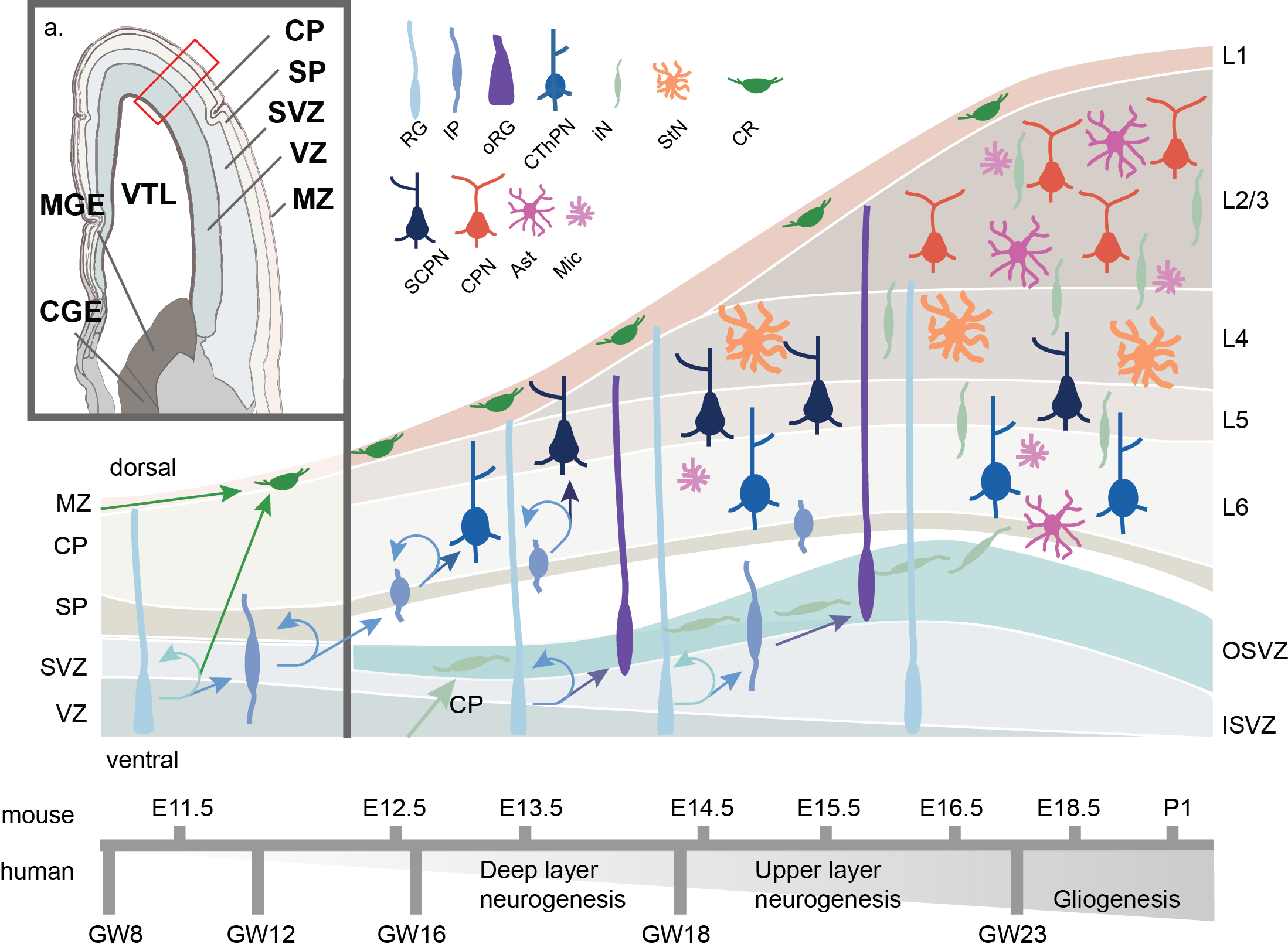

Figure 3. Schematic of human corticogenesis. a) Anatomical view of mid-gestational (GW13) human cortex, adapted from Allen Brainspan imaging (Ziller et al. 2015). CP: cortical plate; SP: subplate; SVZ: subventricular zone; VZ: ventricular zone; MZ: marginal zone; VTL: lateral ventricle; CGE: caudal ganglionic eminence; MGE: medial ganglionic eminence.b) Schematic of cell type transistion, lamination and differentiation through corticogenesis. Radial glia (RG) both self-renew and differentiate to Cajal Retzius (CR) or intermediate progenitors (IP). IPs maintain the ability for self-renewal and differentiate to corticothalamic projecting neurons (CThPN) primarily in layer (L6), subcerebral projecting neurons (SCPN) primarily in L5, stellate neurons (StN) primarily in L4, and cortical projecting neurons (CPN) primarily in L2-3. Later born RG may migrate dorsally into the outer subventricular zone (OSV) where they are known as outer RG (oRG) and develop potential to generate glial cells such as astrocytes (Ast) or microglia (Mic), or remain more ventricular in the inner subventricular zone (ISVZ). Estimated timing of corticogenesis in shown below, with mouse corticogenesis timing in shown on top, and human coticogenesis timing on bottom.

The generation of cortical circuitry is critical. Dysfunction during corticogenesis has been implicated in multiple neurodevelopmental disorders7–9, and evolutionary changes between humans and other apes have been linked to the rapid expansion of the human cortex10. In early embryonic development (GW4 in humans; E10 in mice; where “E’ is embryonic day post conception and “GW” is gestational week), the ectodermal neural tube expands and compartmentalizes into the prosencephalon (forebrain), the mesencephalon (midbrain) and the rhombencephalon (hindbrain)11. The maturing forebrain subdivides along the dorsal-ventral axis into the pallium and subpallium, respectively. The pallium generates the bulk of the cerebral cortex and the subpallium forms the MGE and CGE (Figure 3)12. As the pallium develops, neuroepithelial cells differentiate to RG, named as such for their radial projection from the ventricular zone (VZ) towards the dorsal surface of the pallium, and for their combined marker set of neuroepithelial and astroglial expression patterns13. RG divide asymmetrically, both producing newborn RG to replenish the pool of stem cells, as well as forming intermediate progenitors (IPs) and a subset newborn Cajal-Retzius neurons (CR) directly. However most CR neurons are born exterior to the developing pallium and migrate tagentially into the marginal zone (MZ). IPs move dorsally to populate the subventricular zone (SVZ) while CRs migrate further to develop in the cortical plate (CP). RG continue to mitotically cycle while their nuclei rhythmically move dorsally up the VZ during G2/M phase (basal RG or bRG), and ventrally for/during/in S-phase along cellular projections in a process known as interkinetic nuclear migration (ventricular RG, or vRG; IKNM)13. This process continues through cortical development, with the self-replenishing pool of RG generate IPs and expand the VZ. The process of self-replenishing symmetric divisions and asymmetric neuron generation is partially regulated through the balance of key epigenetic regulators of cells, transcription factors PAX6 and EMX2, respectively14,15. IP cells, not anchored to the apical VZ, populate an outer area of the SVZ, split by an inner fiber layer (IFL), forming outer RG cells (oRG). IPs continue to divide and differentiate forming the cortex in an inside out manner, generating deep layer neurons, then the more superficial layers16. Notably, RG and IPs are known to express messenger RNA (mRNA) associated with deep and superficial layer neurons markers prior to differentiation, though they don’t express the resultant proteins. This is regulated through post-transcriptional repression mechanism and suggests a priming of RG/IPs throughout maturation17. A mature subset of IP, oRG cells form non-neuronal glial cells, such as oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes which permeate across the cortical layers18. In humans, these oRG cells are abundant and self-renew, a characteristic that has been postulated to lead to the human specific cortical expansion19–21. In recent work, differential gene expression of the transcription factor FOXO3 and genes a part of the mTOR pathway have been implicated in oRG formation and self-renewal22,23. After cortical layer formation, RG eventually self-consume into pairs of neurons.

To fully dissect the epigenomic dynamics of corticogenesis, a robust model system is needed. A model system must be both faithful to the subject of study, as well as mutable. Major considerations persist in our ability to understand cortical development both in terms of what may go awry in neurodevelopmental disorders, and what leads to the human-specific expansion of the cortex24. However, the necessary reductionist study to uncover the epigenomic landscape responsible for cortical layer stratification faces major hurdles. First and foremost is sample rarity; human and non-human primate fetal tissue is difficult to obtain. Mouse models lack several key cortical sub-regions and cell types, including the more elaborate organization of progenitors — namely the OSVZ and the oRG found within18. In addition, the developing human cortical plate and subplate, containing CR cells, have distinct cell subtypes missing in mouse1,2. Regions of accelerated mutation since human divergence from chimpanzees reveal the importance of non-coding regions. 92% of human accelerated regions (HARs; 663/721 HARs) fall outside of transcribed sites, and are enriched for enhancer-like activity or transcription-factor binding motifs25. Further, these sites are seen to be active in early embryonic forebrain development25,26. Secondly there is also the need for genetic manipulation. Necessity and sufficiency are largely determined through gene knockout and rescue experiments — corticogenesis is no different. An emerging model system must allow for both genetic manipulation and recapitulate human-specific aspects of development.

Cortical organoids as a model of corticogenesis

Cortical organoids are self-organizing three-dimensional cultures that model features of the developing human cerebral cortex27. They are an adaptation of a 2D cortical “rosette” method that modelled early polarization of neuroepithelial cells and neural tube formation. Induction of human embryonic stem cells (hESC), or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to the ectodermal lineage generates cellular aggregates called embryoid bodies (EBs). Neuroectodermal lineage priming is done through in vitro differentiation of stem cells in decreased basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and a high dose of ROCK inhibitors to limit cell death28,29. From here the protocol deviates from the 2D cortical rosette method to allow for three-dimensional cortical layering. EBs aggregate and are cultured in suspension in a Neurobasal medium with additives to support neural progenitors and their progeny. Shortly thereafter, EBs are embedded into matrigel, an artificial extracellular matrix, which acts as a scaffold for cell migration. EBs expand in the matrigel to form organoids containing fluid-filled cavities reminiscent of brain ventricles, and buds of neuroepithelium that replicate early to mid-gestation of cortical development. Cortical organoids do not form blood vessels and thus as they expand to up to 4 mm in diameter, the diffusion of oxygen and nutrients to the core decreases. This leads to necrotic centers if grown in culture for multiple months. To mitigate necrosis, cortical organoid protocols all feature a form of agitation to facilitate movement of nutrient rich media through the organoids. To achieve this agitation, organoids are cultured in spinning bioreactors30, or on orbital shakers, and previous groups have reportedly maintained organoids in culture for excess of 18 months31. The original organoid protocol did not include cortical region specification and was largely undirected, showing arealization of both the forebrain (FOXG1+), mid brain (OTX1/2+), ventral forebrain (NKX2.1+) and even retinal tissue. Developments in cortical organoids differentiation have revealed that they can be selectively induced to form different brain regions based on small molecule addition to the culture media. For instance, SMAD inhibitors such as dorsomorphin and SB-4321542 induce rapid neural differentiation to the dorsal forebrain state, while retinoic acid presence in early organoid induction is caudalizing30.

Cortical organoids develop in a shorter time frame than native corticogenesis occurs, yet they follow the same cell differentiation progression. Exact times vary by protocol, however a generalized timing is as follows. Within 15-20 days in vitro (DIV15-20, where DIV0 is the original induction of stem cells to ectodermal lineage), cells form continuous neuroepithelia, surrounding fluid-filled cavities (similar to neural rosettes). Pluripotency markers OCT4 and NANOG begin to diminish, while neural identity markers SOX1 and PAX6 increase32,33. By DIV30, a radially organized CP begins to form. This region is positive to pre-plate marker TBR1, and contains RELN expressing CR cells32. Bulk RNA analysis shows at this point that organoids closely resemble prefrontal cortex at GW (gestational week) 8-930. Around DIV60-75, organoids exhibit rudimentary separation between early-born deep layer corticofugal neurons (BCL11B+) and late-born superficial layer (SATB2+, POU3F2+), depending on protocol27,30,31,34. Additionally, it is around this time that the human-specific oRG cells (SOX2+,HOPX+) begin to populate27. Around DIV90-100, organoids become more closely correlated to fetal prefrontal cortex at GW17-2530. Progeny of oRG begin to form astrocytes (GFAP+)30. As organoids age further we begin to see the formation of dopaminergic neurons (TH+) and mature astrocytes (DIV180)35. Organoids in directed protocols that lack a ventral (NKX2.1+ region) did not exhibit interneuron formation27,30,31. However those with the ventral marker showed late formation of interneurons. This is expected, given that interneurons are known to migrate from the ventrally located LGE/MGE during corticogenesis. When cerebral organoids are generated from mouse embryonic stem cells, they lack both the IFL and oRG31. Further supporting evidence that organoid models can recapitulate RG behavior, is a study in which GFP was electroporated, followed by a pulse of BrdU to track lineage divisions in proliferating cells. The authors reported that daughter cells formed after the BrdU pulse chase included both RG and IPs, suggesting this cerebral organoids capture the asymmetric division potential of RG 18.

Organoid cortical models are not without limitations. In RNA comparisons between organoids and primary fetal tissue samples, organoids consistently enrich for genes associated with cellular stress, glycolysis, and electron transport pathways22,24,27. However, it has been demonstrated that this can be alleviated with culturing alterations and is likely induced in the early stages of ectodermal lineage priming of pluripotent stem cells. Organoids transplanted into a mouse cortex appropriated mouse oligodendrocytes and astrocytes, which led to decreased cellular stress signals27. New protocols have introduced vascularization processes to address glycolysis concerns as well36. Xenografted organoids show a higher correlation of radial glia maturation to primary sample age over organoid age22. Further the directed differentiation of organoids is not perfect. Mesodermal linage cells have been uncovered, despite early patterning to the neuroectodermal fate35 and organoids are not homogenous in forebrain cortical area, with many showing both primary visual cortex (V1-like) and prefrontal cortex (PFC-like) signatures22,27. This is partially to be expected given the belief that thalamic input helps define areal signature37,38. Organoids tend to lack the diversity of cell subtypes that form over time in the human cortex27. Despite nuances in organoid differentiation when compared to native human corticogenesis, this model system remains extremely promising for a battery of previously untestable hypotheses and closely resembles early corticogenesis.

References

- Miller, J. A. et al. Transcriptional landscape of the prenatal human brain. Nature 508, 199–206 (2014).

- Hodge, R. D. et al. Conserved cell types with divergent features in human versus mouse cortex. Nature 573, 61–68 (2019).

- Tasic, B. et al. Shared and distinct transcriptomic cell types across neocortical areas. Nature 563, 72–78 (2018).

- Economo, M. N. et al. Distinct descending motor cortex pathways and their roles in movement. Nature 563, 79–84 (2018).

- Lim, L., Mi, D., Llorca, A. & Marín, O. Development and Functional Diversification of Cortical Interneurons. Neuron 100, 294–313 (2018).

- Jäkel, S. & Dimou, L. Glial cells and their function in the adult brain: A journey through the history of their ablation. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 11, 24 (2017).

- Mariani, J. et al. FOXG1-Dependent Dysregulation of GABA/Glutamate Neuron Differentiation in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Cell 162, 375–390 (2015).

- Wang, D. et al. Comprehensive functional genomic resource and integrative model for the human brain. Science 362, eaat8464 (2018).

- Nardone, S. et al. ORIGINAL ARTICLE DNA methylation analysis of the autistic brain reveals multiple dysregulated biological pathways. Transl. Psychiatry 4, e433-9 (2014).

- Herculano-Houzel, S. The remarkable, yet not extraordinary, human brain as a scaled-up primate brain and its associated cost. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, 10661–10668 (2012).

- Stiles, J. & Jernigan, T. L. The basics of brain development. Neuropsychol. Rev. 20, 327–348 (2010).

- Fan, X. et al. Spatial transcriptomic survey of human embryonic cerebral cortex by single-cell RNA-seq analysis. Cell Res. 28, 730–745 (2018).

- Götz, M. & Huttner, W. B. The cell biology of neurogenesis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 6, 777–788 (2005).

- Heins, N. et al. Emx2 promotes symmetric cell divisions and a multipotential fate in precursors from the cerebral cortex. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 18, 485–502 (2001).

- Manuel, M. N., Mi, D., Mason, J. O. & Price, D. J. Regulation of cerebral cortical neurogenesis by the Pax6 transcription factor. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9, 70 (2015).

- Noctor, S. C., Flint, A. C., Weissman, T. A., Dammerman, R. S. & Kriegstein, A. R. Neurons derived from radial glial cells establish radial units in neocortex. Nature 409, 714–720 (2001).

- Zahr, S. K. et al. A Translational Repression Complex in Developing Mammalian Neural Stem Cells that Regulates Neuronal Specification. Neuron 97, 520-537.e6 (2018).

- Lancaster, M. A. et al. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 501, 373–379 (2013).

- Rakic, P. A small step for the cell, a giant leap for mankind: a hypothesis of neocortical expansion during evolution. Trends Neurosci. 18, 383–388 (1995).

- Otani, T., Marchetto, M. C., Gage, F. H., Simons, B. D. & Livesey, F. J. 2D and 3D Stem Cell Models of Primate Cortical Development Identify Species-Specific Differences in Progenitor Behavior Contributing to Brain Size. Cell Stem Cell 18, 467–480 (2016).

- Zhong, S. et al. A single-cell RNA-seq survey of the developmental landscape of the human prefrontal cortex. Nature 555, 524–528 (2018).

- Pollen, A. A. et al. Establishing Cerebral Organoids as Models of Human-Specific Brain Evolution. Cell 176, 743-756.e17 (2019).

- Pollen, A. A. et al. Molecular Identity of Human Outer Radial Glia during Cortical Development. Cell 163, 55–67 (2015).

- Camp, J. G. et al. Human cerebral organoids recapitulate gene expression programs of fetal neocortex development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 15672–7 (2015).

- Capra, J. A., Erwin, G. D., McKinsey, G., Rubenstein, J. L. R. & Pollard, K. S. Many human accelerated regions are developmental enhancers. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 368, 20130025 (2013).

- Pollen, A. A. et al. Establishing Cerebral Organoids as Models of Human-Specific Brain Evolution. Cell 176, 743-756.e17 (2019).

- Bhaduri, A. et al. Cell stress in cortical organoids impairs molecular subtype specification. Nature 578, 142–148 (2020).

- Zhang, S. C., Wernig, M., Duncan, I. D., Brüstle, O. & Thomson, J. A. In vitro differentiation of transplantable neural precursors from human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 1129–1133 (2001).

- Hu, B. Y. & Zhang, S. C. Directed differentiation of neural-stem cells and subtype-specific neurons from hESCs. Methods Mol. Biol. 636, 123–137 (2010).

- Qian, X. et al. Brain-Region-Specific Organoids Using Mini-bioreactors for Modeling ZIKV Exposure. Cell 165, 1238–1254 (2016).

- Lancaster, M. A. & Knoblich, J. A. Generation of cerebral organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 9, 2329–40 (2014).

- Lancaster, M. A. & Knoblich, J. A. Generation of cerebral organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 9, 2329–40 (2014).

- Qian, X. et al. Generation of human brain region–specific organoids using a miniaturized spinning bioreactor. Nat. Protoc. 13, 565–580 (2018).

- Dominguez, M. H., Ayoub, A. E. & Rakic, P. POU-III transcription factors (Brn1, Brn2, and Oct6) influence neurogenesis, molecular identity, and migratory destination of upper-layer cells of the cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex 23, 2632–43 (2013).

- Quadrato, G. et al. Cell diversity and network dynamics in photosensitive human brain organoids. Nature 545, 48–53 (2017).

- Shi, Y. et al. Vascularized human cortical organoids (vOrganoids) model cortical development in vivo. PLOS Biol. 18, e3000705 (2020).

- Cadwell, C. R., Bhaduri, A., Mostajo-Radji, M. A., Keefe, M. G. & Nowakowski, T. J. Development and Arealization of the Cerebral Cortex. Neuron 103, 980–1004 (2019).

- Simi, A. & Studer, M. Developmental genetic programs and activity-dependent mechanisms instruct neocortical area mapping. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 53, 96–102 (2018).