Single cell MET

Motivation

DNA methylation, the covalent addition of a methyl group to cytosine, is known to have critical roles in gene regulation and modifying transcription factor binding affinity. Its role in gene silencing and genomic imprinting is also well studied1,2. Genomic methylation occurs primarily on the approximately 1 billion cytosines in the genome almost exclusively in the context of cytosine-guanine dinucleotides (mC, CG) for most cell types1. DNA methylation is correlated to gene expression3,4 and reflects cellular identity5. DNA methylation has also been linked to neurodevelopmental disorders in the human frontal cortex6. Notably, methylation also occurs at non-CG dinucleotides and is referred to as CH methylation (mCH, H = adenosine, thymine, or cytosine). This is occurs at high levels in embryonic stem cells and mature neurons, though at different trinucleotide patterns, namely CAG for stem cells and CAC for neurons1,7. In mature neurons the amount of mCH exceeds that of mCG during synaptogenesis, roughly four weeks after birth in mice or two years after birth in humans4,8,9. Remarkably, gene body mCH levels in neurons negatively, yet strongly, correlates with transcriptomic expression and are useful for cell type identification10. In bulk methylation profiling of cortical organoids, Luo et al. were able to capture the transition of dominant mCH from CAG to CAC during the transition from neuroepithelial cells to mature neurons, suggesting a point of methylome transition from stem-like to neuronal-like8. This provides both a model system and a key time-point for future analyses of mCH levels and their regulation11. Organoids were observed to have changes in methylome profiling from fetal cortex. These changes manifest as differential methylation across extracellular matrix genes (possibly due to the inclusion of matrigel in culture) and hypomethylation around pericentromeric regions (a previously reported phenomenon for induced pluripotent stem cells)11.

In the native methylation, reduction of mC is catalyzed by the Tet family of mC hydroxylase proteins, converting the methyl- moiety to hydroxymethyl-, formyl-, and carboxyl- progressively. Hydroxymethylation (5hmC) occurs almost exclusively in the CG context and accumulates in mature neurons. In neurons, 5hmC is known to be enriched near constitutively expressed promoter regions4. To this day the role of 5hmC is understudied, likely due to the inability to distinguish mC and 5hmC by the most commonly used assay for methylation, bisulfite conversion. Two reports through alternative assays demonstrate a ratio of 5hmC to mC of 30-50% in mature excitatory neurons4,12. Alternatively, new enzymatic methods have been described in which APOBEC3A, a natively expressed deaminase induces direct cytosine deamination in an in vitro reaction13. To date, this method has not been published as a single-cell protocol, however, it does have a promising adaptation for assaying the understudied moiety 5hmC12.

Method

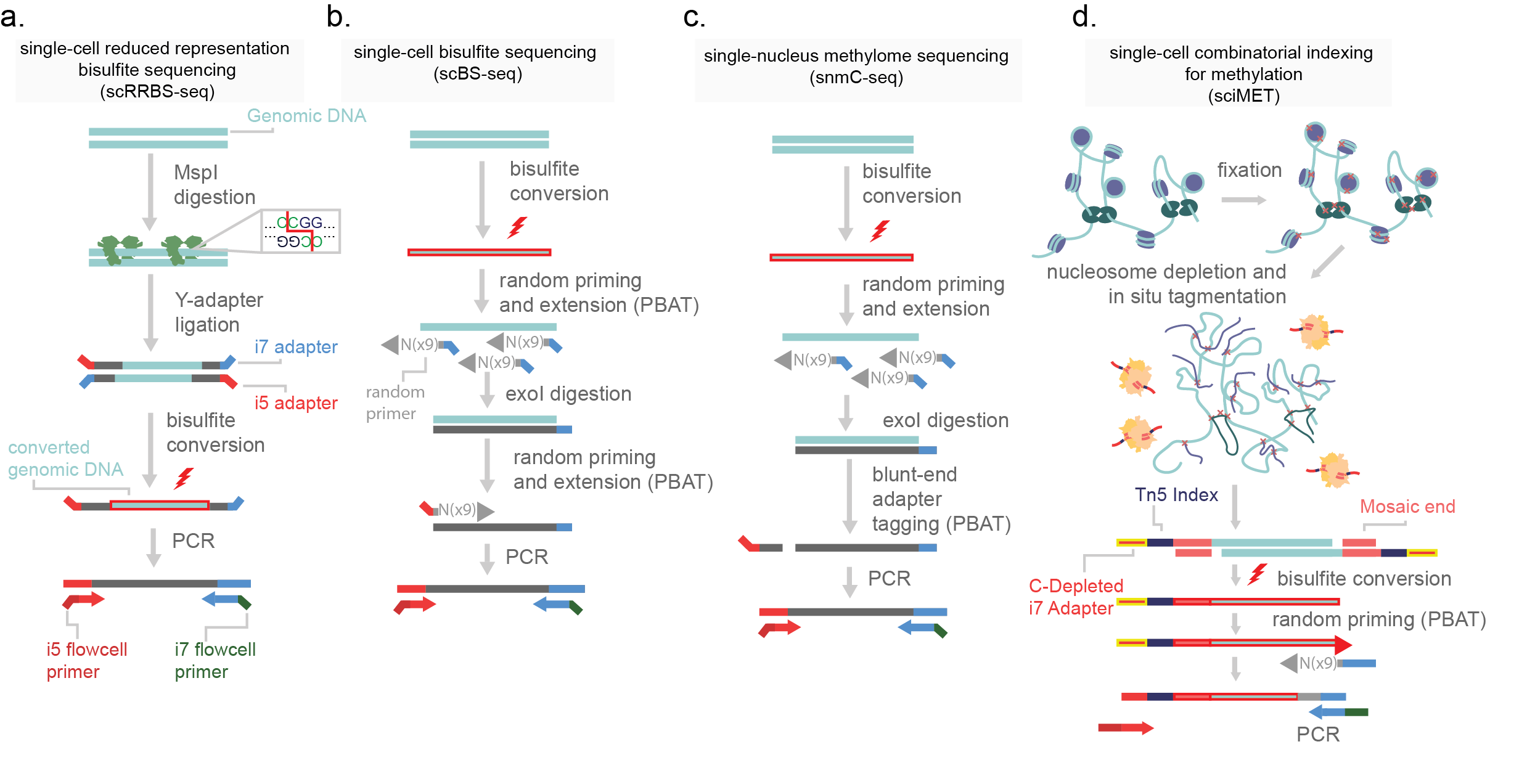

Methylation profiling genome-wide is achieved by the selective mutation of non-methylated cytosines. Sodium bisulfite is applied to genomic DNA which effectively deaminates non-methylated cytosine to uracil, through a three-step reaction. Importantly, uracil complements with adenine, which means subsequent library amplification will report non-methylated cytosines as thymine. Through this point mutation in the reference genome, namely thymine where cytosines were expected, methylation profiles can be inferred (bisulfite-sequencing, BS-seq)14. The first reported protocol for single-cell methylation was scRRBS (reduced representation bisulfite sequencing, Figure 12a). This method uses a methylation-insensitive restriction enzyme (MspI) to digest genomic DNA prior to bisulfite conversion. MspI is used to enrich for CG-rich regions across the genome, via its cut site (5’C|CGG). The resulting sticky ends enriched at CG-rich genome regions are then adapter ligated, DNA is bisulfite converted, and sequencing libraries are prepared15.

Figure 12.Methods for the generation of single-cell methylomes. a) single-cell reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (scRRBS-seq) digests purified genome DNA with restriction enzyme MspI. This enzyme cuts at a CCGG target sites, fragmenting DNA that is in CG rich regions. Y-adapters (pre-annealed i5 and i7 adapters) are then added on by ligation and the molecule is bisulfite converted. Following this, the DNA is then PCR amplified. b) Single-cell bisulfite sequencing bisulfite converts purified genomic DNA and then uses random priming for post-bisulfite adapter tagging. Prior to the second round of random priming, the reaction is incubated with exonuclease I (exoI) which digests single-stranded DNA. This removes excess primer from the reaction. Following this a second round of random priming is used to introduce the next adapter and the molecules are PCR amplified. c) Single-nucleus methylome sequencing (snmC-seq) is similar to scBS-seq but uses a blunt-end adapter tagging strategy. d) Single-cell combinatorial indexing for methylation (sci-MET) uses a C-depleted oligonucleotide loaded onto a Tn5 enzyme to tagment nucleosome depleted nuclei. Following this, cells are lysed, bisulfite converted, and a post-bisulfite adapter tagging strategy is used prior to PCR amplification.

BS-seq is harsh and fragments genomic DNA. This is of high concern for scaling the assay to single-cell resolution. To avoid heavy losses of genomic capture, post-bisulfite adapter tagging (PBAT) is used. In PBAT library adapters necessary for PCR and sequencing are added to genomic DNA after BS conversion (Figure 11b)5,10,16. In this order of events, BS conversion fragments the genome and denatures DNA to a single-stranded state. Single-cell PBAT strategies such as scBS-seq introduce adapters after conversion through random priming, similar to the single-cell whole genome method DOP-PCR16,17. Secondary adapters are then added and libraries can be sequenced. An alternative approach, single-nucleus methylome sequencing (snmC-seq), uses a blunt-end adapter tagging strategy (Figure 12c)10. Cells are fully lysed by the bisulfite conversion chemical reaction, making this protocol difficult but not impossible to adapt to higher cell count strategies. I detail a new method for high throughput single-cell methylome library generation (sci-MET). In this method I use custom sequencing adapters and indexes depleted in cytosines. The lack of cytosines prevents BS conversion changing the indexes, allowing for the split-pool indexing necessary for sci- chemistry (Figure 12d).

Analysis

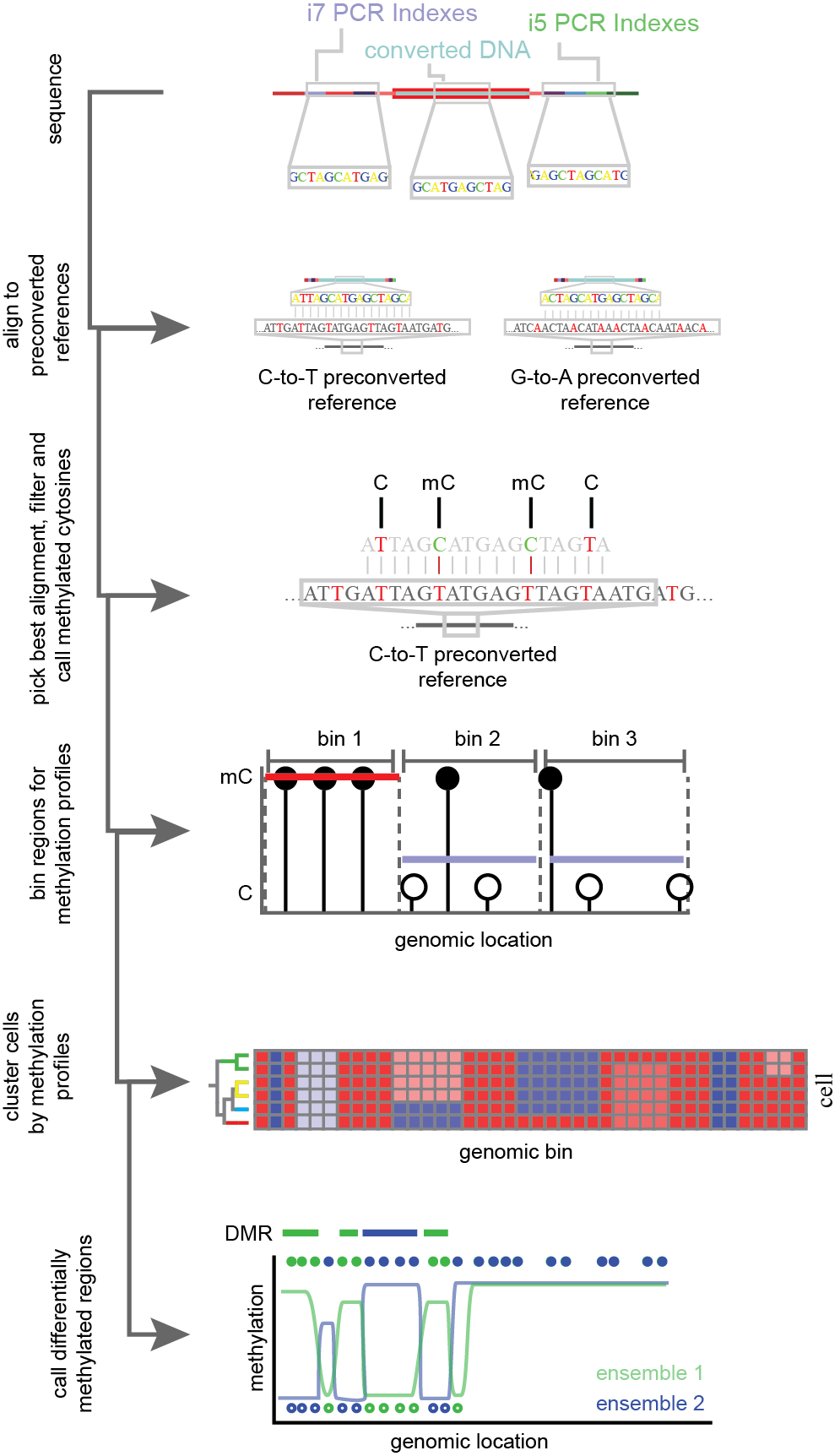

Figure 13.Simplified flow through of single-cell methylation analysis. Bisulfite converted and PCR amplified DNA is sequenced and aligned to pre-converted reference genomes. C-to-T and G-to-A conversions are performed to account for bottom and top strand library capture. For the most confident mapping location and strand, cytosines (C) and methylated cytosines (mC) are called based on point mutations induced in bisulfite conversion. Methylation profiles for cytosines are aggregated over genomic regions and used to group single-cells into clusters. Cells are combined within clusters for increased power and changes in methylation across the genome are calculated.

Analysis of single-cell methylation profiles leverage the point-mutations induced through BS conversion. These mutations lead to decreased library complexity and can make reference alignment difficult. To account for this, special considerations must be taken. In one approach, the tool Bismark18 generates four pre-converted reference genomes to account for the full bisulfite treatment of each possible strand of genomic DNA prior to running the short read sequence aligner Bowtie19. From this, base specific methylation of cytosines can be ascertained. Alignments with greater than 70% methylation of non-CG cytosines reported as methylated are generally removed from analysis as this suggests a read-specific failure of bisulfite conversion10. Following filtering, methylation rates (% methylated CG/all CG) are generated across genomic bins and used for dimensionality reduction and clustering. To account for depth of coverage, some strategies apply a post-hoc probabilistic binomial model, wherein region methylation rates are weighted by coverage16. Notably, for neuronal data, CH methylation rates performs better for discrimination of cell types than CG methylation rates10. Differentially methylated regions have been implicated as diagnostic biomarkers20, and can be calculated between cellular clusters via two-sided t-tests (Figure 13)21. High throughout single-cell methods will allow for exploratory analyses of methylome changes across complex systems such as neurodevelopment or tumor progression. It is with this motivation in mind that we developed sci-MET.

References

- Lister, R. et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature 462, 315–322 (2009).

- Bird, A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes and Development 16, 6–21 (2002).

- Clark, S. J. et al. scNMT-seq enables joint profiling of chromatin accessibility DNA methylation and transcription in single cells. Nat. Commun. 1–9 doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03149-4

- Lister, R. et al. Global epigenomic reconfiguration during mammalian brain development. Science (80-. ). 341, (2013).

- Farlik, M. et al. Single-Cell DNA Methylome Sequencing and Bioinformatic Inference of Epigenomic Cell-State Dynamics. Cell Rep. 10, 1386–1397 (2015).

- Jaffe, A. E. et al. Mapping DNA methylation across development , genotype and schizophrenia in the human frontal cortex. 19, 4–7 (2016).

- Lee, J. H., Park, S. J. & Nakai, K. Differential landscape of non-CpG methylation in embryonic stem cells and neurons caused by DNMT3s. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–11 (2017).

- Luo, C. et al. Cerebral Organoids Recapitulate Epigenomic Signatures of the Human Fetal Brain Resource Cerebral Organoids Recapitulate Epigenomic Signatures of the Human Fetal Brain. CellReports 17, 3369–3384 (2016).

- Guo, J. U. et al. Distribution, recognition and regulation of non-CpG methylation in the adult mammalian brain. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 215–22 (2014).

- Luo, C. et al. Single-cell methylomes identify neuronal subtypes and regulatory elements in mammalian cortex. Science (80-. ). 357, 600–604 (2017).

- Luo, C. et al. Cerebral Organoids Recapitulate Epigenomic Signatures of the Human Fetal Brain. Cell Rep. 17, 3369–3384 (2016).

- Schutsky, E. K. et al. Nondestructive, base-resolution sequencing of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine using a DNA deaminase. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 1083–1090 (2018).

- Feng, S., Zhong, Z., Wang, M. & Jacobsen, S. E. Efficient and accurate determination of genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in Arabidopsis thaliana with enzymatic methyl sequencing. Epigenetics and Chromatin 13, 42 (2020).

- Frommer, M. et al. A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5- methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89, 1827–1831 (1992).

- Guo, H. et al. Profiling DNA methylome landscapes of mammalian cells with single-cell reduced-representation bisulfite sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 10, 645–659 (2015).

- Smallwood, S. a et al. Single-cell genome-wide bisulfite sequencing for assessing epigenetic heterogeneity. Nat. Methods 11, 817–20 (2014).

- Miura, F., Enomoto, Y., Dairiki, R. & Ito, T. Amplification-free whole-genome bisulfite sequencing by post-bisulfite adaptor tagging. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e136–e136 (2012).

- Krueger, F. & Andrews, S. R. Bismark : a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. 27, 1571–1572 (2011).

- Langmead, B., Trapnell, C., Pop, M. & Salzberg, S. L. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10, R25 (2009).

- Jensen, S. Ø. et al. Novel DNA methylation biomarkers show high sensitivity and specificity for blood-based detection of colorectal cancer- A clinical biomarker discovery and validation study. Clin. Epigenetics 11, 158 (2019).

- Assenov, Y. et al. Comprehensive analysis of DNA methylation data with RnBeads. 11, (2014).